![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/6/csm_07-DP00459-2023BC_Kopie_21216b4c93.jpg)

Since its founding in 1999, Typotheque has been stirring up the international typography scene: with its fonts, the type foundry not only gives form to language but often also pushes the boundaries of technology. Countless international awards have honoured this commitment, as has the Kunstmuseum (Art Museum) in The Hague, which in 2019 dedicated its only typography exhibition to date to Typotheque’s work. And when the founder and creative director Peter Biľak was labelled a “game changer” by the architecture magazine Metropolis for his contribution to non-Latin typography, it implied that the creative mind thinks far beyond pure typographic craft.

Interview with Typotheque

Red Dot: “November” was created in cooperation with 60 designers from all over the world. How did this come about?

Typotheque: As communication becomes more global, we lack tools to ensure cross-cultural and international exchange. For example, there was no font for the Indigenous communities of northern Canada, and no fonts with more styles for some languages in India. We decided to approach all living languages as we approach our own language – by creating fonts that support them in a respectful way, while respecting the highest standards in design and technology. This is much needed work, not only for global companies, but also for under-represented language communities.

What was the biggest challenge of this project?

We came to understand why others don’t engage with world languages – it entails very time-consuming research. When designing a Latin or Greek font, you can consult books or websites on those languages, but that doesn’t work for Asian or African languages. We had to travel to distant places, visit archives, look for historical sources, interview people and understand the related technological limitations. Current font development tools do not easily support the complex languages of India, for example, so we had to develop new production workflows.

How many languages does November cover?

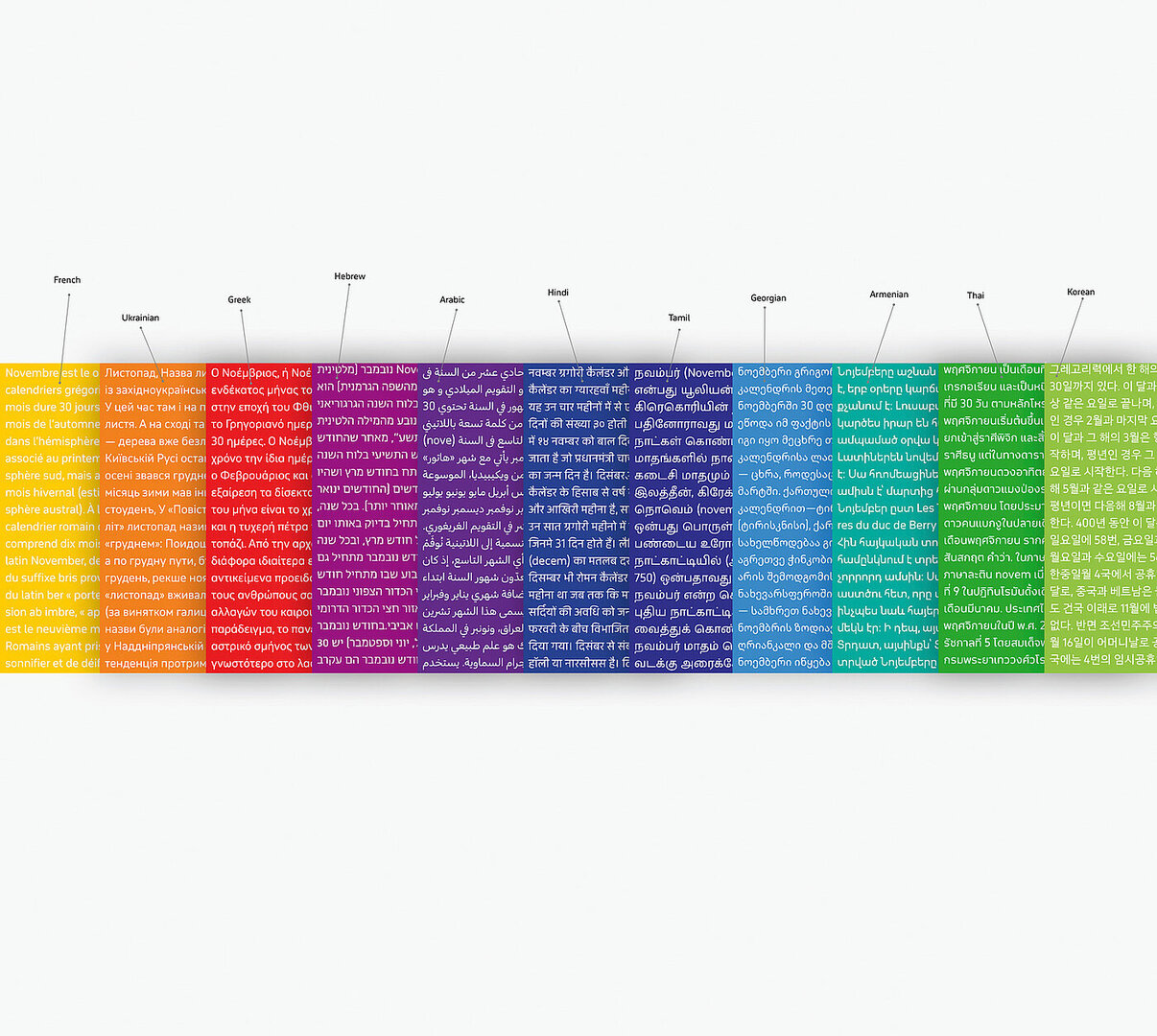

We have looked at all living languages in the world but started with those spoken by the largest groups of people. In India, where there are some 418 languages, we first focused on the officially recognised languages and then set the threshold for inclusion of a writing system at 0.1 per cent of the population. Currently, November comprises 27 script systems covering hundreds of languages and over 90 per cent of the world’s population.

November took eight years to develop. How did you manage to persevere?

The motivation that kept us going was the impact of this project. I have experienced situations where people literally burst into tears when they saw their names written correctly for the first time. We do not take this responsibility lightly, and it is very motivating to see how our work can contribute to the preservation of languages.